Why PBS is harmful for Autistic and Neurodivergent young people (Part 2)

We’re joined by guest contributor, Helen Edgar, for Part 2 of her ‘AGAINST PBS & ABA’ campaign blog. Helen continues to explore the harmful impact PBS can have on Neurodivergent young people and suggests alternatives that centre autonomy and consent.

Compliance is not connection and one of the most harmful myths of PBS is the belief that reward systems build positive relationships.

For Neurodivergent children, relational trust isn’t built through praise or stickers, it’s built through attunement, empathy, and consent.

True connection happens when children feel seen, heard, and respected, not managed and controlled. Conditional acceptance based on behaviour set up against neuronormative ideals teaches Autistic children that their worth is tied to performance. They learn to mistrust adults and suppress their authenticity. For many Autistic young people, especially those with a ‘Pathological Demand Avoidance’ (PDA) profile, or those aligned with monotropism, external rewards may feel irrelevant or even undermining.

As the Therapist Neurodiversity Collective points out, behaviourist models presume motivation comes from external validation. But many Autistic people are intrinsically motivated, led by interest (monotropic), led by their sensory needs and their ethical values. PBS fails to respect our inner worlds as Autistic people, focusing instead on observable outcomes and ‘compliance’ rather than connection or understanding.

PBS punishes difference

At it’s core, PBS doesn’t just ignore Neurodivergent ways of being; it actively invalidates a person’s Autistic identity. Behaviours that help Autistic people regulate, such as stimming, moving, communicating, working and playing in different ways, are often actively discouraged or punished within PBS frameworks. I’ve seen sensory tools removed for being ‘misused’, meltdowns labelled as defiance, and children being labelled ‘naughty’ when in overwhelm.

In these moments, distress is often misinterpreted as disruption and the child (or even the parent/carer) is often blamed and their autonomy is dismissed. This is especially harmful for those already vulnerable to biased interpretations, such as children with learning disabilities, those from minority backgrounds, and those who don’t communicate in expected neuronormative ways. PBS often reinforces ableism and systemic injustice. The Culture of Care Statement (2024) highlights that Black children are disproportionately targeted by restrictive behaviour systems, which often misread culturally valid communication as deviance. What is framed as neutral ‘support’ often upholds systems of racism and ableism.

Consent and autonomy matter

Neuroaffirming practice needs to centre autonomy and consent. That means respecting a child’s ‘no’, listening to their body language and sensory needs and responding to their right to disengage when needed. It means supporting diverse communication methods and understanding that regulation can look very different for Autistic people and that co-regulation and interdependency are equally valid.

PBS undermines a young person’s autonomy and right to consent at every level. It teaches children that adults know better than they do, that their bodies can’t be trusted, and their instincts must be controlled at all times. When we teach children to ignore their own minds and bodies in order to gain approval, we are teaching them that they don’t matter and they can’t trust themselves.

What counts as ‘evidence’?

PBS is often described as ‘evidence-based’, but this claim needs a bit of a deeper dive. Much of the evidence around PBS and ABA relies on adult observers interpreting a child’s external behaviour and rarely includes Autistic voices. As NICE guidelines (NG11) caution, the evidence for ABA-style interventions is limited, and reliance on behavioural outcomes can be misleading.

Organisations and work from the Culture of Care and the Therapist Neurodiversity Collective argue that PBS research is outdated and misaligned with the neurodiversity paradigm. Evidence without lived experience is not reflective of the real inner experiences and needs of Autistic people. We need frameworks that centre the people that are being supported, not just those in charge of implementing interventions.

What are the alternatives?

We need to build something better than PBS for our young people that doesn’t cause harm.

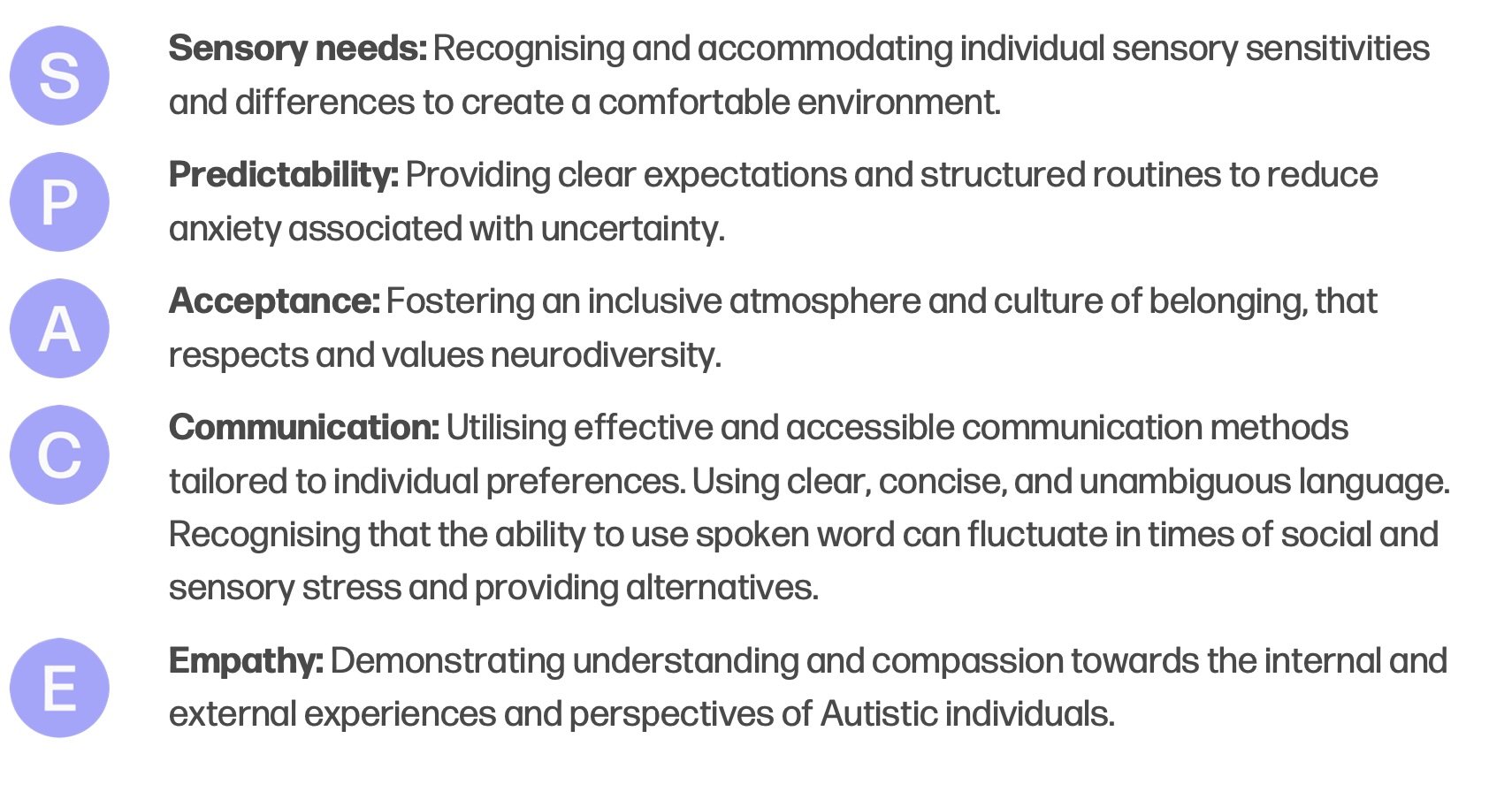

The SPACE Framework (Doherty, McCowan & Shaw, 2023) is one example of an alternative that offers a hopeful neuroaffirmative approach.

The SPACE Framework

Doherty, McCowan, & Shaw, (2023)

We need to consider what a child needs to feel safe and connected, rather than looking at ways to change their behaviour. When we shift our thinking and change the environment instead of the person, we can create space for trust, safety, well-being and learning.

Embracing authentic Autistic identity and thriving

PBS is not a neutral tool, it is situated in a behaviourist framework that is based on compliance, not care. PBS teaches children to mask, mistrust their bodies and minds, and to only equate their value with performance.

Autistic and Neurodivergent children do not need fixing: they need environments that honour their differences. They need safe spaces where they are listened to, respected, and supported to discover their true identity and be their authentic, Autistic selves.

We need to move away from PBS and instead foster spaces and communities rooted in consent, curiosity, and compassionate care. Our focus should not be on managing and controlling Autistic young people, we need to build trust and understanding. We need to create spaces where young people can flourish and feel safe, where their needs are met. By rejecting PBS and ABA we can create and build alternative supportive frameworks where young people can feel proud of their true Autistic identity and can thrive as they grow up.

References

Doherty, M., McCowan, S., & Shaw, S.C.K. (2023). Autistic SPACE: A novel framework. British Journal of Hospital Medicine, 84(4). https://www.magonlinelibrary.com/doi/full/10.12968/hmed.2023.0006

NICE (2015). Challenging behaviour and learning disabilities: prevention and interventions (NG11). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng11

Culture of Care (2024). PBS Position Statement. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/632462bb88e23c400c82d41a/t/6853da4d52d6893f5a1ad68c/1750325838447/CofC+PBS+Position+Statement+V5.pdf